Home

A comprehensive resource for safe and responsible laser use

2003 FAA simulator study

An August 2003 U.S. Federal Aviation Administration study found that when pilots are illuminated by laser light, it is significantly more difficult for them to successfully land an airplane.

Test procedure

Thirty-four volunteer pilots each flew four “short-final” approaches in an FAA Boeing 727 flight simulator. During three of the approaches, at 100 feet altitude a green laser was aimed at the simulator cockpit window for one second, using one of three exposure levels: 0.5 µW/cm² (microwatts per square centimeter), 5.0 µW/cm² or 50 µW/cm². During one of the four approaches, no laser was used.

These photos from the FAA study illustrate the four test scenarios. The scenarios were randomly chosen; for any given approach, the pilot would not know what laser exposure (if any) he or she would experience.

No laser exposure. This gives a baseline for a “normal” approach.

0.5 µW/cm²: This corresponds to a 5 mW (milliwatt) laser pointer at 3,700 feet, or a 50 mW pointer at 2.2 miles.

5.0 µW/cm²: This corresponds to a 5 mW pointer at 1,200 feet, or a 50 mW pointer at 3,800 feet.

50 µW/cm²: This corresponds to a 5 mW pointer at 350 feet, or a 50 mW pointer at 1,100 feet. The animation simulates flashblindness and a slowly fading afterimage.

(For a real-world laser exposure which looks remarkably similar to these photos, see this photo taken from a helicopter. Higher-resolution still photos of the above animations are available here: no laser exposure, 0.5 µW/cm², 5.0 µW/cm², 50 µW/cm².)

All exposures were eye-safe. The study wanted to see if safe but “too bright” light would interfere with pilot performance during critical tasks such as landing an aircraft.

Results

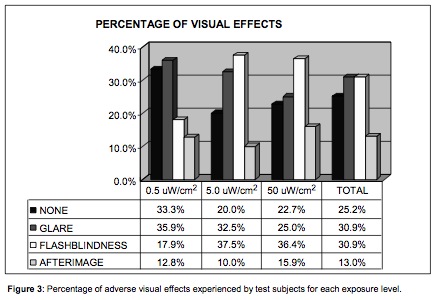

The chart below shows how the laser light affected the pilots:

Even at the dimmest light level (0.5 µW/cm²), two-thirds of the responses indicated a visual effect: 35.9% glare, 17.9% flashblindness, and 12.8% afterimage. For the two brighter exposures, over a third of the responses indicated the pilots were briefly flashblinded. (Note: A subject could list no effect, one effect, or more than one effect. Therefore, percentages were calculated based on the total number of reported effects, not on the number of subjects.)

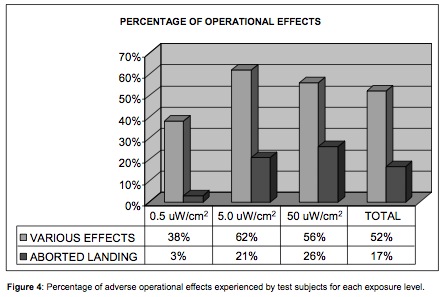

Regarding performance, about 75% of the pilots had “some degree of operational difficulty.” This included aborted landings, relinquishing command to the co-pilot, and other “operational and visual performance problems.” The chart below shows the percentage of operational effects and aborted landings at the various intensity levels.

Summary

Even eye-safe levels of laser light were found to be distracting during a “short-final” approach. The two higher levels studied, 5.0 and 50 µW/cm², were found to be significantly more troublesome for pilots than the lowest level (0.5 µW/cm²). This was demonstrated by reports of adverse effects more than half of the time, and a 20-25% rate of aborted landings. In conclusion, the FAA study shows that exposure to very low levels of laser light can adversely affect a pilot’s performance on short-final approach.

Implications for pilots

The study indicated that, after one or two exposures, pilots grew familiar with the limitations of a laser exposure. This caused less worry and better performance:

“Once they realized that the duration of the laser exposures were brief, several pilots commented that they were less concerned about the laser’s influence on their performance. Consequently, they became increasingly comfortable flying, even while visually impaired, during and immediately after exposure.... Acquainting pilots with low-level laser exposure could minimize its effects and reduce the chance of an extreme reaction.”

“Post-flight comments indicated that familiarization with the effects of laser exposure, instrument training, and recent flight experience in the aircraft type may be important factors in enhancing a pilot’s ability to successfully cope with laser illumination at eye-safe levels of exposure.”

Implications for laser pointer users

The exposures in this study were very short (just 1 second) and relatively dim (50 to 5000 times lower than Class 3A exposure limits). Some laser enthusiasts may think that this is a reasonable light level: “I can easily handle this, so professional pilots should not have a problem.” However, the study found that pilots clearly had problems including aborted landings. Thus, the effects of laser light on a pointer enthusiast may not be the same as the effects on a pilot concentrating on landing a commercial aircraft.

In addition, the FAA pilots were in a simulator and knew they would be illuminated by a laser. A pilot in a real aircraft, surprised by an unexpected light flash, would probably have even more difficulty in reacting.

Links

- Additional information on the four FAA photos showing the cockpit view of laser light. Higher-resolution versions of the FAA photos (the best available to LaserPointerSafety.com) are available here: no laser exposure, 0.5 µW/cm², 5.0 µW/cm², and 50 µW/cm².

- The FAA study: “The Effects of Laser Illumination on Operational and Visual Performance of Pilots During Final Approach”, DOT/FAA/AM-04/9, US DOT FAA Office of Aerospace Medicine, August 2003. Study produced by Van Nakagawara, Ronald Montgomery, Archie Dillard, Leon McLin and Capt. Bill Connor.

- “Laser Illumination of Pilots in the National Airspace System” PowerPoint presentation by Van Nakagawara (lead author of the above study), addressing the plenary session of the International Laser Safety Conference, March 2009 in Reno, NV. Gives an overview of the issue of laser/aviation safety. Contains statistics on laser incidents by year, region, time of day, etc.