Home

A comprehensive resource for safe and responsible laser use

Tips for using lasers with pets and other animals

Eye safety

Just as you should not point a laser beam at any person’s eyes or face, you also should not point a laser beam at an animal’s eyes or face. The beam could cause eye injury.

This is especially important if you have a handheld laser with a power that may be over the limit for laser pointers. This limit is 1 milliwatt (mW) in most countries and 5 mW in the U.S.

Unfortunately, pointers or handhelds may sometimes be mislabeled. For this reason, always use caution. Assume the beam is more powerful and hazardous than the label states.

Prevent the direct or reflected laser beam from going in any person’s eye or any animal’s eye.

Known cases of eye injury

We are unaware of any cases of pets with eye injury caused by their owners using laser pointers. Of course, an animal cannot communicate whether they are seeing spots or are having vision trouble, though serious vision degradation would cause noticeable behavioral problems.

If you are aware of any animal eye injury cases, please email us with the information, link, etc. The email address is below, at the bottom of this page.

Behavioral concerns

It can be fun for an owner to watch their pet dog or cat chasing a laser pointer. But continued use of the laser pointer can be frustrating for the animal. There is nothing for them to catch.

You can simulate a catch somewhat, by turning off the beam when the animal puts a paw over it or otherwise would capture the dot if it was a real-world object.

You can also use the laser pointer to help the animal find treats or items you’ve hidden. In this case, there is a tangible reward after following the laser dot.

Experts caution against using laser pointers with pets

Dr. Karen London, a certified animal behaviorist and author of five books on canine training, has written a blog post recommending against laser pointers for dogs:

- “Laser pointer chasing can lead to serious behavioral issues…. The constant chasing without ever being successful at catching the moving object can frustrate dogs beyond anything they should have to tolerate…. There are many cases of dogs who were diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder after (and perhaps partly as a result of) this activity…. No matter how much dogs respond to them, I recommend against the use of laser pointers. It’s just too likely that the game will negatively affect the dog.”

This is echoed by the American Kennel Club:

- “Unfortunately, a game of laser pointer chase can be very frustrating for a dog and can lead to behavioral problems. The movement of a laser pointer triggers a dog's prey drive, which means they want to chase it. It's an unending game with no closure for the dog since they can't ever catch that beam of light, like they can when chasing a toy or food. Many dogs continue looking for the light beam after the laser pointer has been put away; this is confusing for your dog because the prey has simply disappeared. This can create obsessive compulsive behaviors like frantically looking around for the light, staring at the last location they saw the light, and becoming reactive to flashes of light (such as your watch face catching the sunlight and reflecting on the wall, or the glare of your tablet screen on the floor). Dogs that exhibit behavioral issues are frustrated, confused, and anxious.”

Cat behaviorist Jackson Galaxy, host of Animal Planet’s TV series “My Cat From Hell”, has similar cautions regarding cats:

- “Successful play therapy provides satisfaction on all levels of predation: not just stalking, but catching and "killing" as well. When the pointer is used as the sole toy, the cat never actually CATCHES anything… If they can't catch "the dot," and the dot is put away at your convenience, then there will be an “inappropriate victim” down the line: other cats in the house, or your ankles as you walk by. It’s like winding up a jack-in-the-box and expecting the top not to blow off. If used as the only toy in the cat's play life, the laser pointer can actually help promote further play aggression, and undo the benefits of play therapy.”

A 2021 article in the journal "Animals" described a scientific study which found a correlation between using laser pointers and abnormal repetitive behaviors in cats:

- "Laser light play alone … does not allow cats to complete the hunting sequence; cats cannot ‘catch’ the prey. It has been suggested that this might trigger frustration and stress, both of which can contribute to compulsive behaviors….which may be connected to laser light play: chasing lights or shadows, staring “obsessively” at lights or reflections, and fixating on a specific toy. The [study's] results, although correlational, suggest that laser light toys may be associated with the development of compulsive behaviors in cats, warranting further research into their use and potential risks." From Kogan, L.R.; Grigg, E.K. Laser Light Pointers for Use in Companion Cat Play: Association with Guardian-Reported Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors. Animals 2021, 11, 2178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11082178

An internet search for phrases such as “are laser pointers bad for dogs” or “cats laser pointers” will turn up numerous sources that do not recommend using laser pointers to play with pets. In some anecdotal cases, a person’s dog became unhealthily obsessed with the laser light after the first session.

Technical considerations about animal eye sensitivity

For humans, there has been extensive research on how the eye responds to laser light. This has led to safety standards and concepts such as the Maximum Permissible Exposure. The MPE tells how much laser light, at what wavelength and for what exposure time, is considered safe.

Much of this research was done on primate eyes. So for primates, the human eye MPEs would be valid.

However, we are unaware of any research specifically to develop eye MPEs for dogs, cats, birds and other pets and wildlife.

Said another way, we don’t know if these animals’ eyes are more or less sensitive to laser light, compared to human eyes.

We do know that some animals have much better night vision than humans. But that does not necessarily mean that they are more sensitive to laser light. After all, these animals also have day vision meaning that they can withstand high levels of sunlight.

For animal eye safety, the best advice is simply to keep laser beams away from animals’ eyes, just as you would avoid people’s eyes.

Additional technical speculations

Consider how an animal’s retina, pupil, and lens is similar to, and different from, that of a person.

- Retina: Animal retinal tissue is primarily water — the same as human retinas. It is likely the thermal limits would be similar. In other words, the same amount (irradiance) of laser light that can cause injury to a human retina, is likely to also cause a similar injury to an animal retina.

- Lens: The focusing ability of the human eye is probably as good as or better than most animals. This is specifically referring to the ability to focus light down to a point. Once a lens can focus light to a diffraction-limited point, it can’t get any sharper than that. (While some animals may have better eyesight (resolution), this would be due to more cones in the retina — like having more pixels on a screen.)

- Pupil diameter: An animal with a larger pupil than a human would let in more light, but only if the laser beam diameter is larger than the pupil diameter. Obviously, if the laser beam is very narrow such as 2 or 3 mm wide, then all of the light could enter the pupil whether it is 7 mm diameter like in a dark-adapted human or 12.5 mm like in a dark-adapted cat. But if the laser beam is wide, say 13 mm, then a cat’s pupil would let in more of that laser’s light than would a human pupil.

In conclusion, an animal’s retina would probably have a similar sensitivity to laser light as a human eye, and the lens would focus to a similar spot size. The main difference is if the pupil is larger; it would let in more light.

Human safety standards such as the Maximum Permissible Exposure assume a 7 millimeter diameter pupil aperture. This is the size when dark adapted.

An animal with a larger pupil than a human could be more susceptible to laser eye injury 1) if the eye is dark adapted or otherwise has a pupil larger than 7 mm diameter and 2) if the laser beam’s area is larger than the pupil. A larger pupil will allow more light to pass through to the retina.

Cat pupil size, and laser safety speculations

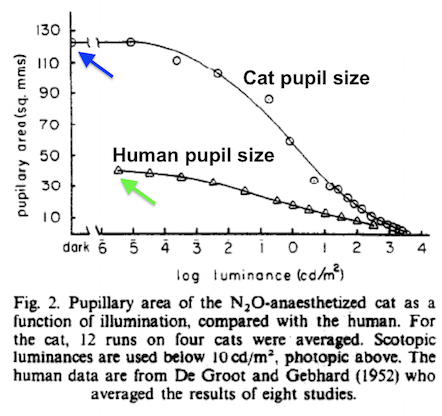

A 1975 paper by Wilcox and Barlow, “The size and shape of the pupil in lightly anesthetized cats as a function of luminance,” states that the scotopic (dark-adapted) cat pupil’s area is 123 mm² (12.5 mm diameter), while the scotopic human pupil area is 40 mm² (7.1 mm diameter).

The chart shows this; the blue arrow is the largest dark-adapted cat pupillary area of 123 mm²; the green arrow is the largest dark-adapted human pupillary area of 40 mm². As the room light gets brighter (increasing luminance), the pupil of each species constricts to block out the light.

This means that a cat’s eye can let in three times the light of a human eye. This implies that the “cat MPE” would be three times lower than that of the human MPE (assuming that a cat retina has the same thermal damage threshold as a human retina and that a cat lens focuses to the same sharpness as a human lens).

For an unintentional exposure of 1/4 second, where it is assumed a person would blink or turn away, the human MPE for visible light is 2.54 milliwatts per sq. cm. This further implies that the cat MPE for a 1/4 second exposure would be in the neighborhood of 0.8 mW/cm².

There is one other factor that may be relevant. Cats have a reflective layer behind the retina, called the tapetum lucidum. This bounces light back to the rods and cones, increasing night sensitivity by 44%. That’s why cats’ eyes glow when illuminated by sources such as a flashlight, car headlights or a camera flash.

Laser light would also be reflected and intensified by the tapetum lucidum. That would mean that cats’ eyes would be even more susceptible to laser light injuries. Instead of 0.8 mW/cm², the cat MPE would be 44% less or about 0.5 mW/cm².

Note: The above are back-of-the-envelope speculative calculations intended to give a rough estimate of cat vs. human sensitivity to laser light. No one should rely on these to determine what a “safe” laser exposure would be for a cat.

Bird pupil considerations

The following are offered as starting points for consideration of how bird eyes might be affected by laser light to a greater or lesser degree than human eyes.

The Wikipedia “Bird vision” page states the following:

- “….small birds are effectively forced to be diurnal [active in daylight] because their eyes are not large enough to give adequate night vision…. Birds of prey are diurnal because, although their eyes are large, they are optimized to give maximum spatial resolution rather than light gathering, so they also do not function well in poor light.”

According to Wikipedia there are significant differences between diurnal birds, which include birds of prey, and nocturnal birds, which include owls:

- “Diurnal birds of prey: The visual ability of birds of prey is legendary, and the keenness of their eyesight is due to a variety of factors. Raptors have large eyes for their size, 1.4 times greater than the average for birds of the same weight,[9] and the eye is tube-shaped to produce a larger retinal image. The resolving power of an eye depends both on the optics, large eyes with large appertures suffers less from diffraction and can have larger retinal images due to a long focal length, and on the density of receptor spacing. The retina has a large number of receptors per square millimeter, which determines the degree of visual acuity…. The raptor's adaptations for optimum visual resolution (an American kestrel can see a 2–mm insect from the top of an 18–m tree) has a disadvantage in that its vision is poor in low light level, and it must roost at night.”

- “Nocturnal birds: Adaptations to night vision include the large size of the eye, its tubular shape, large numbers of closely packed retinal rods, and an absence of cones, since cone cells are not sensitive enough for a low-photon nighttime environment. There are few coloured oil droplets, which would reduce the light intensity, but the retina contains a reflective layer, the tapetum lucidum. This increases the amount of light each photosensitive cell receives, allowing the bird to see better in low light conditions.”

In an article describing how eagles have better vision than humans, the author states “Eagles are able to benefit from larger pupil size and cone density because they have a clearer cornea and lens. Also they can change the shape of their cornea as well as their lens for fine focusing and to account for aberrations.”

The human retina has blood vessels on the surface of the retina. One benefit is that these help carry away excess heat buildup from bright light or laser light that is on the retina. Birds, however, have a structure called the pecten which has “a greatly reduced number of blood vessels.” Perhaps bird retinas would have a greater sensitivity to injury without as many blood vessels.